People who argue about the definition of roguelikes are annoying, but what if they're right?

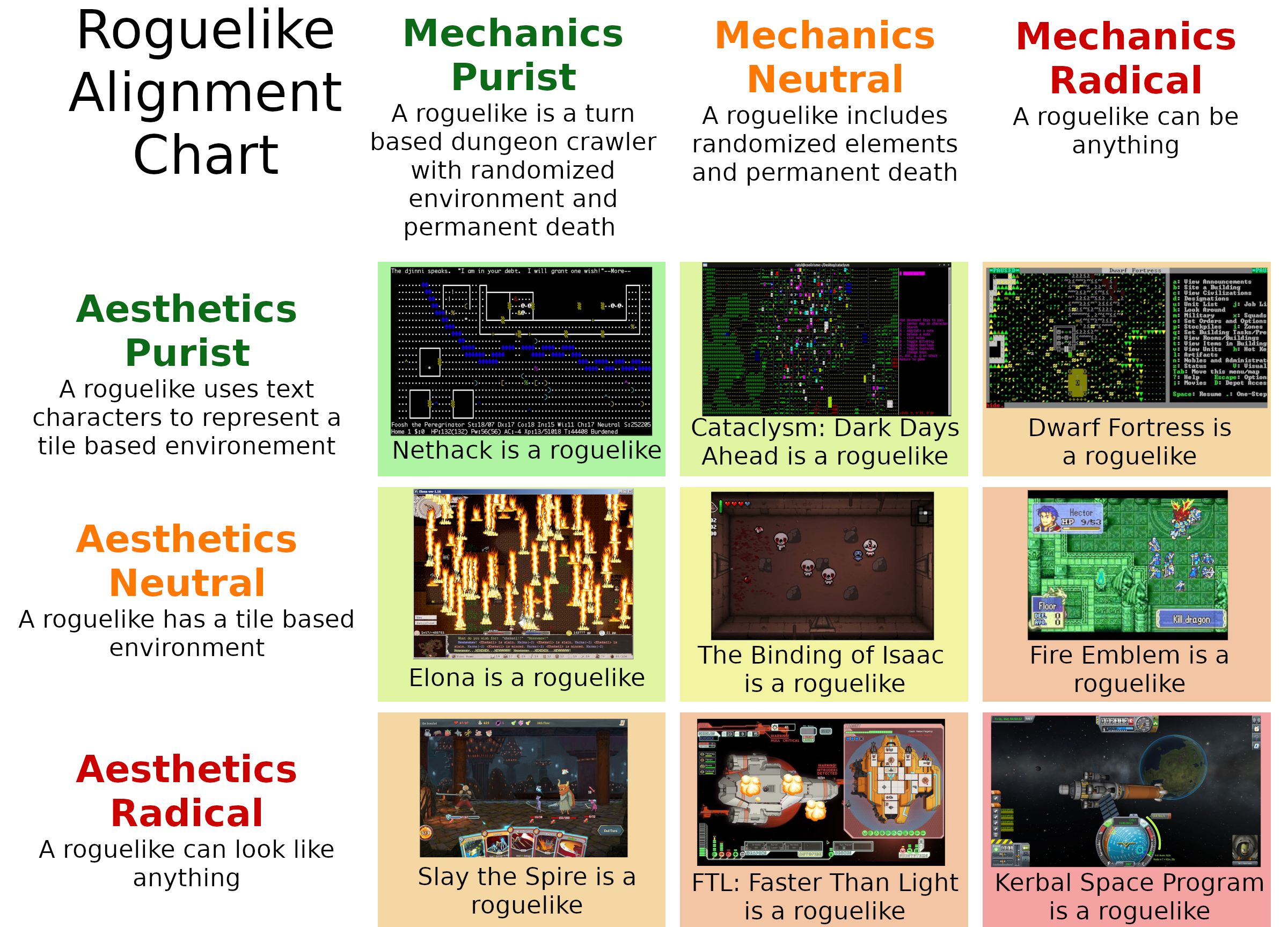

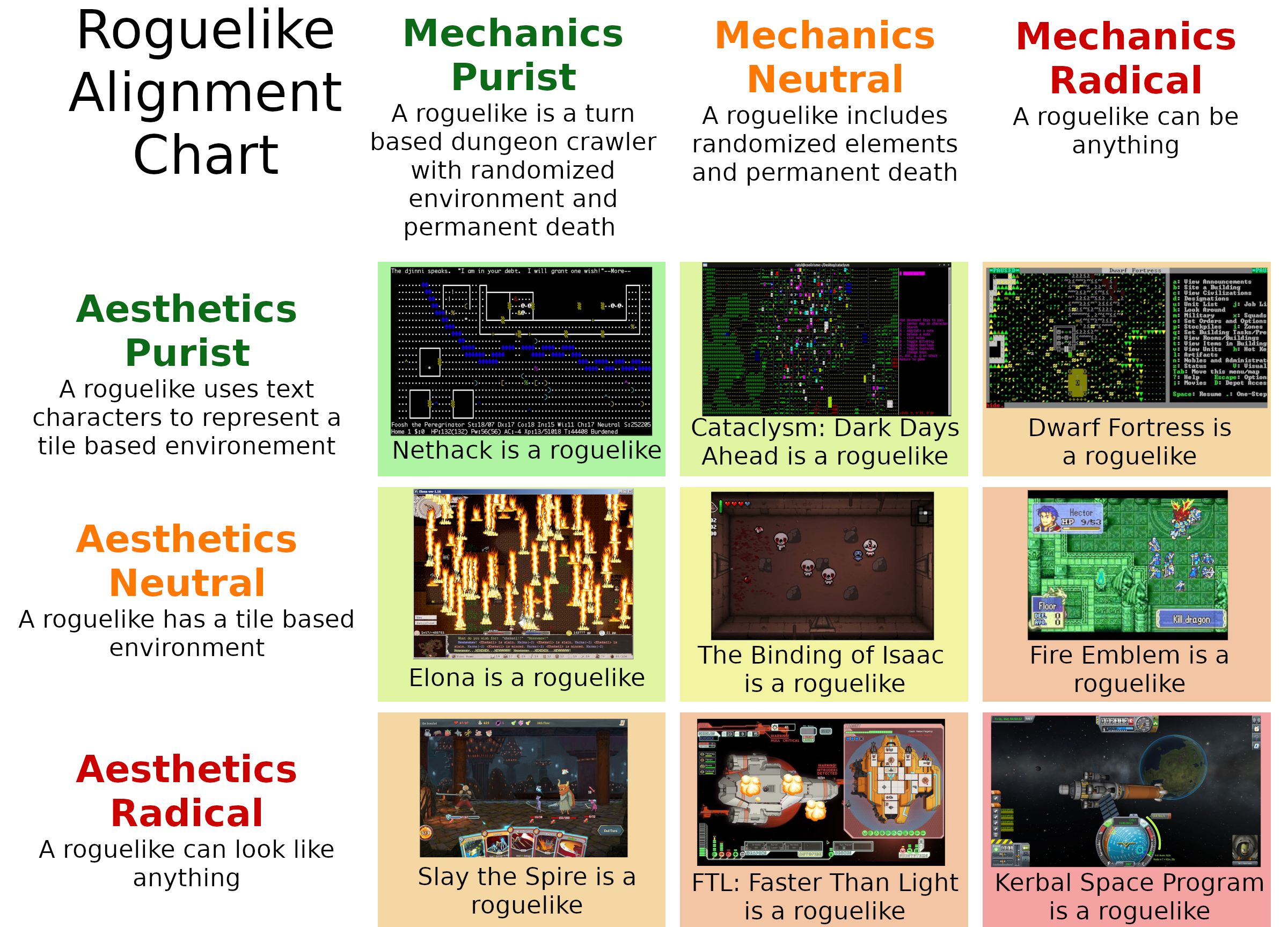

The top upvoted post in the history of r/roguelikes is—what else?—a taxonomy. "MECHANICS PURIST, MECHANICS NEUTRAL, MECHANICS RADICAL," reads the vertical categories of a six-boxed matrix. "AESTHETICS PURIST, AESTHETICS NEUTRAL, AESTHETICS RADICAL," occupy the hash marks.

Somewhere on this grid, within the grist of semantics and glossology, you can identify your own personal definition of the roguelike doctrine. An aesthetics purist and a mechanics radical? Then you probably think the ASCII city-building epic Dwarf Fortress is a roguelike. An uncompromising arch-conservative? Then you're sticking with Nethack and Ancient Domains of Mystery. A pallid centrist? Fine, The Binding of Isaac is a roguelike.

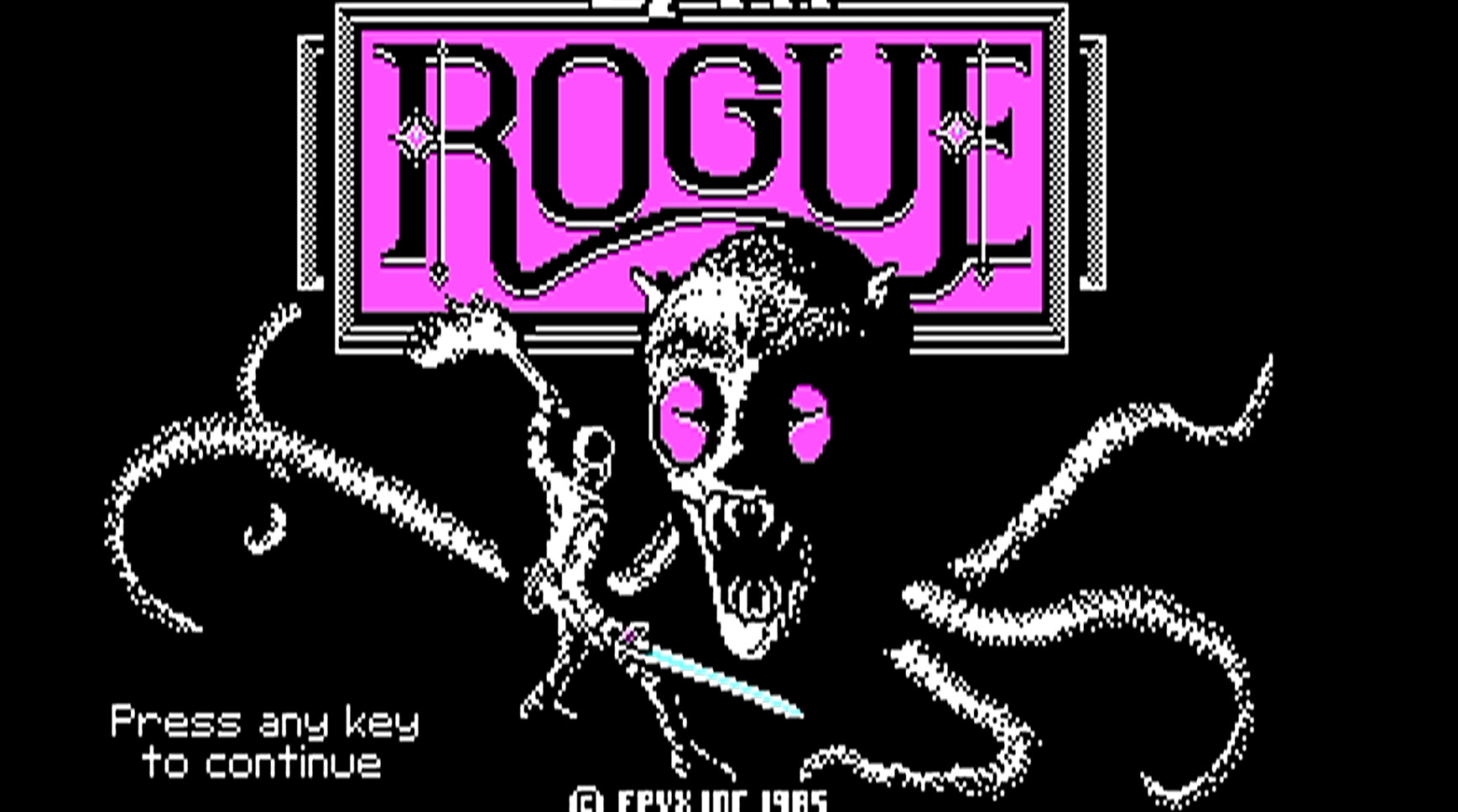

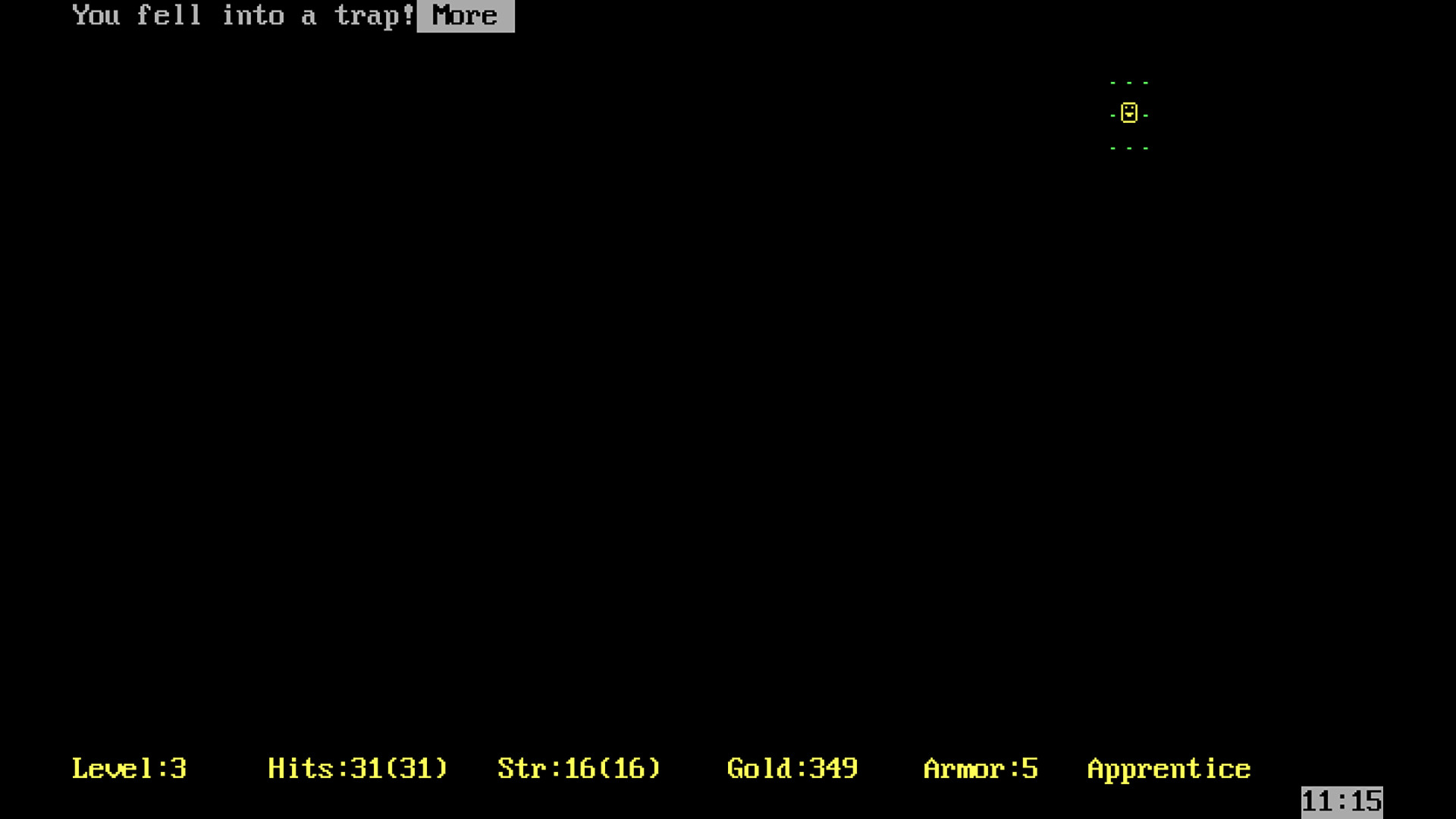

What do these distinctions mean? Well, in the most traditional sense, a "roguelike" is a turn-based dungeon crawler with permadeath, a wide degree of interaction, and an unyieldingly prehistoric art style. The further you deviate from that form—toward a card game like Slay The Spire or a platformer like Spelunky—the more you'll aggrieve a core group of roguelike reactionaries. Genre wars are as old as pop culture itself. Pick any fractious fraternity—electronic dance music, left politics, film noir—and you will find long, nocturnal forum threads adjudicating the composite factors that add up into, say, a true acid house track.

But for my money, there is no community more insoluble than that of roguelike grognards. First-person shooter fans might argue in favor of the precision of Counter-Strike or the bedlam of Call of Duty, strategy gamers might choose sides between 4X grand campaigns and tight corridor tactics modules, but those divisions tend to be glib and light-hearted in nature. Civ vs X-Com could never approach the ontological friction of Roguelike Nation.

In 2008, at the International Roguelike Development Conference, a group of enthusiasts established a written creed called "The Berlin Interpretation" that aimed to legitimize the tenets of an authentic roguelike once and for all. Naturally, peace didn't prevail, and obstinate arguments have raged ever since.

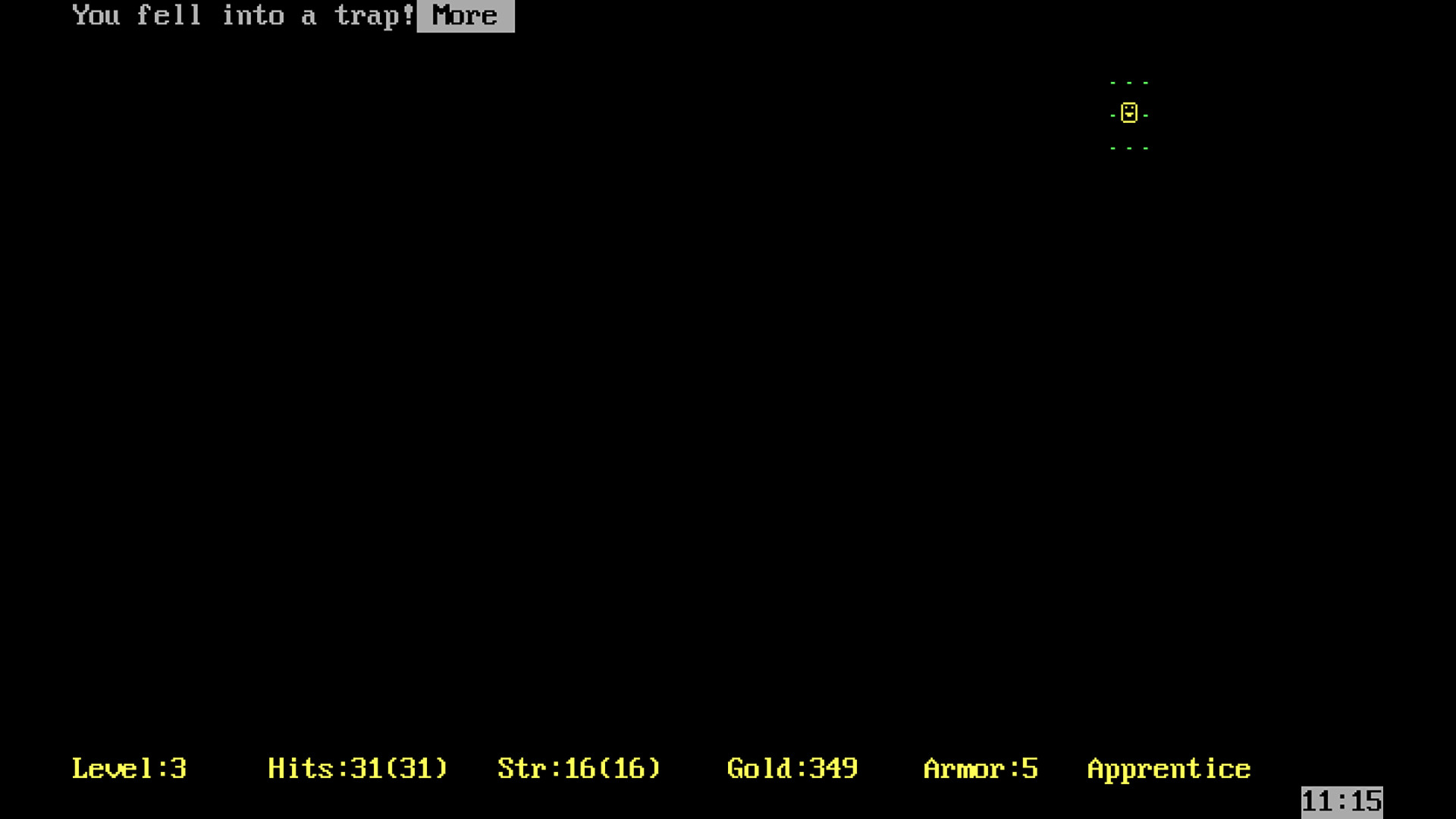

High-value factors: random environment generation, permadeath, resource management (such as food and potions), exploration and discovery; gameplay that's turn-based, grid-based, hack'n'slash, and non-modal, meaning actions available in combat should be available during any other state (exceptions are made for the overworld in ADOM and ]shops in Crawl).

Low-value factors: ASCII display, dungeons, a single player-character, tactical challenge, rules applying to monsters in the same way as the player, and visible numeric values for player-character stats.

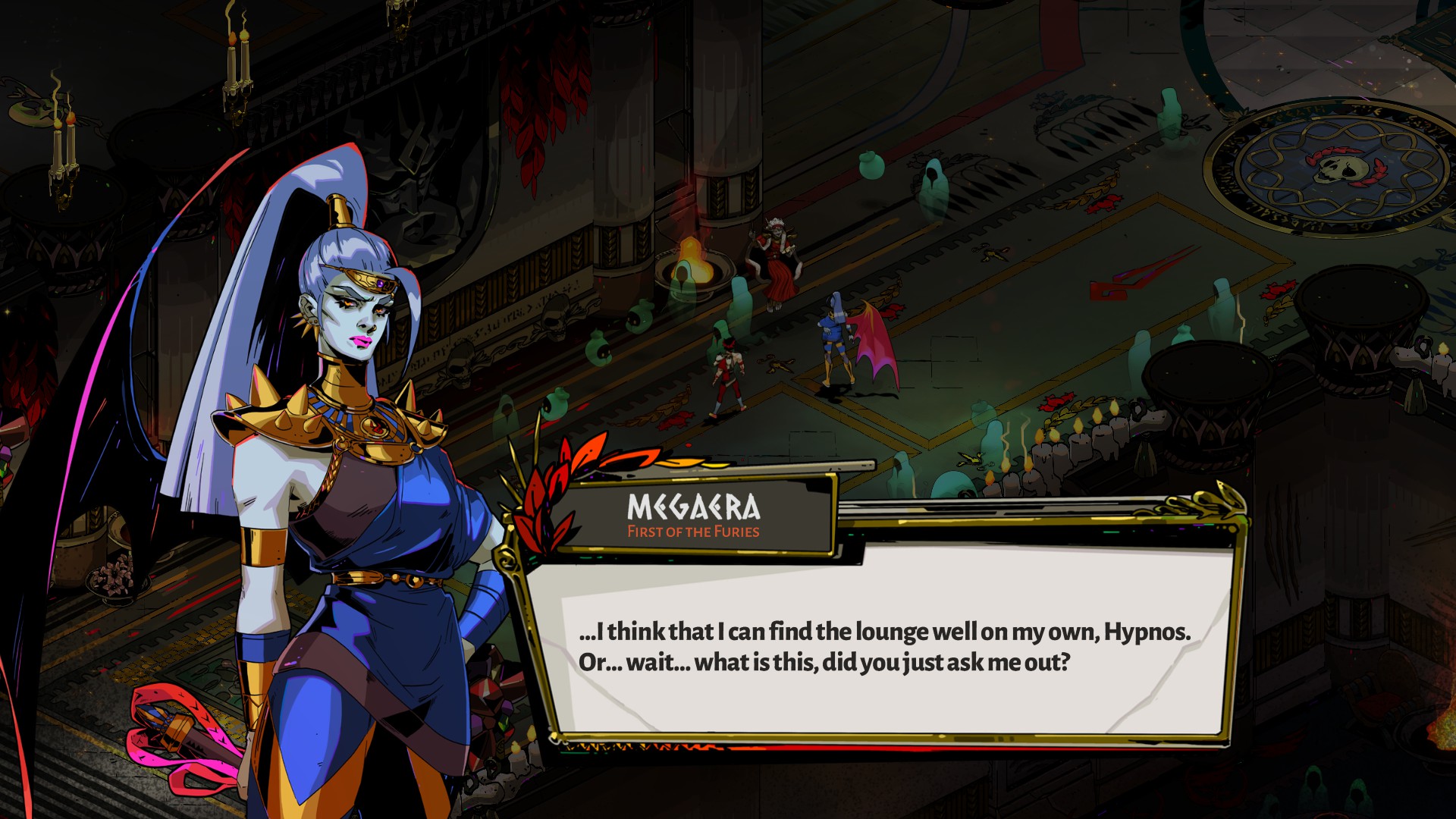

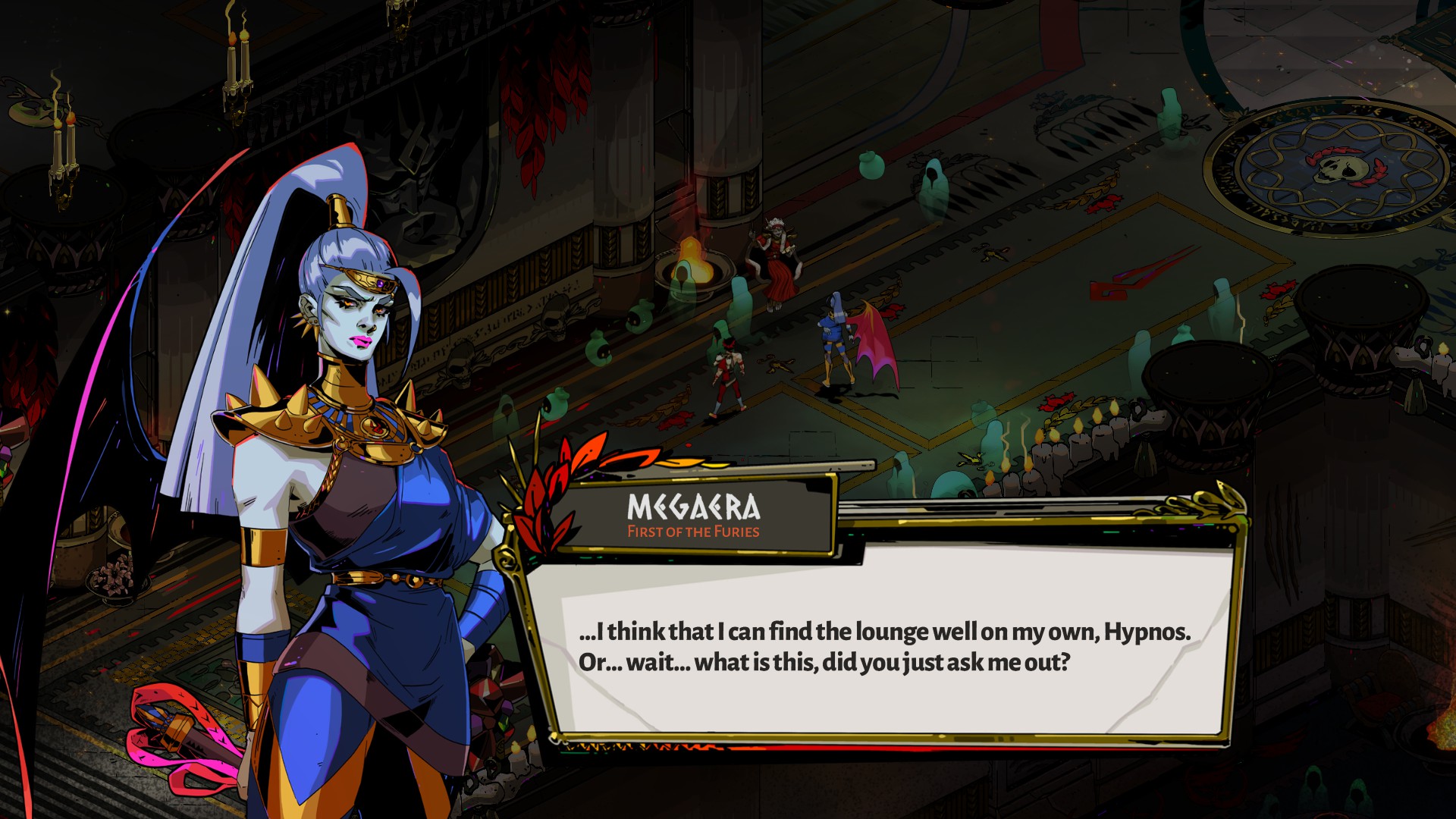

In fact, at this point, a crucial part of being into roguelikes is to carry on a constant dialogue about what a roguelike is. Hardcore devotees have gone as far to devise a separate subclassification to keep the genre pure. "Roguelites," they say, include meta-progression and real-time combat a la Hades, and true roguelikes would never appease the player in that way. (In the past, the term used for those games was the even more cumbersome, "Roguelikelike.")

Jeremiah Reid, the creator of the gothic roguelike Golden Krone Hotel, parodied a recurring interaction he witnessed on r/roguelike in his blog. A bright-eyed gamer wanders into the forum, and sparks a discussion about whatever False Roguelike they're currently enjoying, like Darkest Dungeon or Rogue Legacy, only to get shouted down by the dedicated posters.

"This poor soul, not having the first fucking clue about the decade long debate over the word roguelike, innocently shares their love and asks for recommendations", writes Reid. "A flamewar erupts. Every confused comment from the OP makes things worse and they are downvoted into oblivion... They are screamed at, called names, told to leave, and they usually do."

Look, gamers are pedantic, and it's pretty easy to get annoyed by pickled, gatekeeping attitudes in any community. But I've always wanted to hear the roguelike lifers out. The passion for the purity of the genre transcended the grievances I became accustomed to in my communities of choice. There was something spiritual here that I never encountered in my monthly dose of Hearthstone grousing. What do they think they're losing as roguelikes stray further from their stringent origins? Why is genre sanctity worth defending to the death?

...there is no one clear definition of what a roguelike is, so it's naturally evolving over time

Josh Ge

Josh Ge, a roguelike developer and one of the moderators of both r/roguelike and r/roguelikedev, responded to my email. He is a self-avowed, but goodhearted member of the old guard, and has graciously waded into the roguelike demarcation debates in the past. (Check out this article he published last year, where he wrestles with that monolithic question, "What is a traditional roguelike?") Ge has grown exhausted of the chronic metaphysical flame wars, and tells me that the moderation team on the forum essentially banned discussions on the "nature of roguelikes" earlier this year. But clearly, says Ge, this is a topic that cuts deep. It's not so much about dogma or one-upmanship, he explains. Instead, as the rest of the world catches on with roguelikes that don't fit the original criteria—as Hades racks up Game of the Year awards—this issue becomes about identity.

"We had a perfectly fine term for this genre for a couple decades and there is a certain loss of identity when a mainstream majority starts using that term to mean something rather different and we can no longer use it to have the same meaning it once had, at least not without considering the audience," says Ge. "That's part of what got us here in the first place, that there is no one clear definition of what a roguelike is, so it's naturally evolving over time based on its use by different parties, and the speed of that evolution has accelerated considerably in the last five years!"

That point is echoed by Darren Grey, another moderator of the r/roguelike subreddit who also hosts the Roguelike Radio podcast. He made a point that forced me to consider how the emerging mainstream interpretation of the genre might be more incongruous with the original text than us normies fully understand. Grey was first drawn to roguelikes because he never had any interest in twitchy, input-heavy games. Not now, and not when he first started gaming. "I'm a conservative in terms of games I like. I have close to zero interest in anything that requires reflexes," he says. "Such games just don't do it for me, except maybe in social settings." With that in mind, consider how someone like Grey would receive Enter The Gungeon—a bullet hell gauntlet that asks for precise dodges, marksmanship, and cover negotiation—when it gets christened as a roguelike. If Grey considers that to be heresy, I'm not going to be the person who tells him he's wrong.

"There was a period of time in the late '90s and '00s in particular where it felt like games were just becoming pretty interactive movies. Roguelikes offered a severe break from that, where the aesthetics didn't matter, the mechanics had incredible depth, and the focus was entirely on the gaming experience. You had to get to know the game properly yourself and master it with your very own brain cells," says Grey. "Real-time gameplay is usually a big divider for classic roguelike fans, as it fundamentally changes the gameplay."

Roguelikes are a type of game that you can really get obsessive about

Darren Grey

Grey gets especially annoyed when he pages through the roguelike filter on Steam, and watches the keyword fill up with games that he has no personal use for. That alone is a strong argument for a partition in the terminology—to establish an orthodoxy to permanently separate the Likes and Lites—but as the catalogue swells, it's also undeniable proof that the old guard is growing increasingly outmoded. There are still plenty of people developing classic roguelikes, but it is undeniable that games like Dead Cells are slowly but surely redefining the term. Grey notes that Hades probably has more players than the entire ASCII roguelike contingency as a whole. It's a losing battle.

"This puts people on the defensive, generating a sort of cultural siege mentality," says Grey. "If you only want to play turn-based games that prioritise thought over reflexes it is now far far harder to find appealing games amidst the noise. It would just be easier if all this new stuff was called something else."

Still, people like Grey are a long way from conceding ground. That's one of the ironies about the traditional roguelike community; for as tedious as these taxonomic deliberations can be, they're destined to continue on forever. It's almost as if there is an enduring faith that with enough ink, and podcasts, and Reddit threads, the community could eventually find a definitive genre truth that everyone could settle on. Maybe that's due to the nature of roguelike game design—which as we've expressed, is bound by a number of fiddly dogmas that don't hinder the other tabs on Steam. (Though the moderators I spoke to both expressed how a similar contentiousness could've existed for FPSes in an alternate history, if they were still being called "Doomclones" in the 21st century.) But Ge has an alternative theory. Maybe roguelike lifers are eager to compartmentalize their videogames, because roguelike lifers have something in common on a genetic level.

"The propensity to discuss this particular topic in so much detail also likely stems from the type of players who enjoy traditional roguelikes in the first place, a pretty analytical, detail-oriented bunch," says Ge. "A huge portion of which are themselves programmers or at least work in IT fields and are big on breaking things down and categorizing them as part of a problem-solving process."

Ge is right. There is certainly a prickly, restless exterior to the average hardcore roguelike fan, and their coterie has been stricken with a confrontational impulse for a long time. But don't let that scare you off. Trust me, for as exclusionary and defensive as this community can appear, the denizens of r/roguelike genuinely love these games—and despite the anxiety, they want you to love them too. (You know, as long as you're playing on their terms.) Could Roguelike Nation be a little kinder to newbies and a little more lenient on some of their more hard-line demands? Probably, but they're the last flag bearers of a tradition worth holding on to, and they take that seriously.

"Roguelikes are a type of game that you can really get obsessive about, and that's not very frequent among single player games. In the whole field of gaming they represent the biggest set of cerebrally-focused challenges," says Grey. "Whatever we end up calling the classic roguelike genre, it shouldn't be forgotten."

from PCGamer latest https://ift.tt/3fX3AsX

The top upvoted post in the history of r/roguelikes is—what else?—a taxonomy. "MECHANICS PURIST, MECHANICS NEUTRAL, MECHANICS RADICAL," reads the vertical categories of a six-boxed matrix. "AESTHETICS PURIST, AESTHETICS NEUTRAL, AESTHETICS RADICAL," occupy the hash marks.

Somewhere on this grid, within the grist of semantics and glossology, you can identify your own personal definition of the roguelike doctrine. An aesthetics purist and a mechanics radical? Then you probably think the ASCII city-building epic Dwarf Fortress is a roguelike. An uncompromising arch-conservative? Then you're sticking with Nethack and Ancient Domains of Mystery. A pallid centrist? Fine, The Binding of Isaac is a roguelike.

What do these distinctions mean? Well, in the most traditional sense, a "roguelike" is a turn-based dungeon crawler with permadeath, a wide degree of interaction, and an unyieldingly prehistoric art style. The further you deviate from that form—toward a card game like Slay The Spire or a platformer like Spelunky—the more you'll aggrieve a core group of roguelike reactionaries. Genre wars are as old as pop culture itself. Pick any fractious fraternity—electronic dance music, left politics, film noir—and you will find long, nocturnal forum threads adjudicating the composite factors that add up into, say, a true acid house track.

But for my money, there is no community more insoluble than that of roguelike grognards. First-person shooter fans might argue in favor of the precision of Counter-Strike or the bedlam of Call of Duty, strategy gamers might choose sides between 4X grand campaigns and tight corridor tactics modules, but those divisions tend to be glib and light-hearted in nature. Civ vs X-Com could never approach the ontological friction of Roguelike Nation.

In 2008, at the International Roguelike Development Conference, a group of enthusiasts established a written creed called "The Berlin Interpretation" that aimed to legitimize the tenets of an authentic roguelike once and for all. Naturally, peace didn't prevail, and obstinate arguments have raged ever since.

High-value factors: random environment generation, permadeath, resource management (such as food and potions), exploration and discovery; gameplay that's turn-based, grid-based, hack'n'slash, and non-modal, meaning actions available in combat should be available during any other state (exceptions are made for the overworld in ADOM and ]shops in Crawl).

Low-value factors: ASCII display, dungeons, a single player-character, tactical challenge, rules applying to monsters in the same way as the player, and visible numeric values for player-character stats.

In fact, at this point, a crucial part of being into roguelikes is to carry on a constant dialogue about what a roguelike is. Hardcore devotees have gone as far to devise a separate subclassification to keep the genre pure. "Roguelites," they say, include meta-progression and real-time combat a la Hades, and true roguelikes would never appease the player in that way. (In the past, the term used for those games was the even more cumbersome, "Roguelikelike.")

Jeremiah Reid, the creator of the gothic roguelike Golden Krone Hotel, parodied a recurring interaction he witnessed on r/roguelike in his blog. A bright-eyed gamer wanders into the forum, and sparks a discussion about whatever False Roguelike they're currently enjoying, like Darkest Dungeon or Rogue Legacy, only to get shouted down by the dedicated posters.

"This poor soul, not having the first fucking clue about the decade long debate over the word roguelike, innocently shares their love and asks for recommendations", writes Reid. "A flamewar erupts. Every confused comment from the OP makes things worse and they are downvoted into oblivion... They are screamed at, called names, told to leave, and they usually do."

Look, gamers are pedantic, and it's pretty easy to get annoyed by pickled, gatekeeping attitudes in any community. But I've always wanted to hear the roguelike lifers out. The passion for the purity of the genre transcended the grievances I became accustomed to in my communities of choice. There was something spiritual here that I never encountered in my monthly dose of Hearthstone grousing. What do they think they're losing as roguelikes stray further from their stringent origins? Why is genre sanctity worth defending to the death?

...there is no one clear definition of what a roguelike is, so it's naturally evolving over time

Josh Ge

Josh Ge, a roguelike developer and one of the moderators of both r/roguelike and r/roguelikedev, responded to my email. He is a self-avowed, but goodhearted member of the old guard, and has graciously waded into the roguelike demarcation debates in the past. (Check out this article he published last year, where he wrestles with that monolithic question, "What is a traditional roguelike?") Ge has grown exhausted of the chronic metaphysical flame wars, and tells me that the moderation team on the forum essentially banned discussions on the "nature of roguelikes" earlier this year. But clearly, says Ge, this is a topic that cuts deep. It's not so much about dogma or one-upmanship, he explains. Instead, as the rest of the world catches on with roguelikes that don't fit the original criteria—as Hades racks up Game of the Year awards—this issue becomes about identity.

"We had a perfectly fine term for this genre for a couple decades and there is a certain loss of identity when a mainstream majority starts using that term to mean something rather different and we can no longer use it to have the same meaning it once had, at least not without considering the audience," says Ge. "That's part of what got us here in the first place, that there is no one clear definition of what a roguelike is, so it's naturally evolving over time based on its use by different parties, and the speed of that evolution has accelerated considerably in the last five years!"

That point is echoed by Darren Grey, another moderator of the r/roguelike subreddit who also hosts the Roguelike Radio podcast. He made a point that forced me to consider how the emerging mainstream interpretation of the genre might be more incongruous with the original text than us normies fully understand. Grey was first drawn to roguelikes because he never had any interest in twitchy, input-heavy games. Not now, and not when he first started gaming. "I'm a conservative in terms of games I like. I have close to zero interest in anything that requires reflexes," he says. "Such games just don't do it for me, except maybe in social settings." With that in mind, consider how someone like Grey would receive Enter The Gungeon—a bullet hell gauntlet that asks for precise dodges, marksmanship, and cover negotiation—when it gets christened as a roguelike. If Grey considers that to be heresy, I'm not going to be the person who tells him he's wrong.

"There was a period of time in the late '90s and '00s in particular where it felt like games were just becoming pretty interactive movies. Roguelikes offered a severe break from that, where the aesthetics didn't matter, the mechanics had incredible depth, and the focus was entirely on the gaming experience. You had to get to know the game properly yourself and master it with your very own brain cells," says Grey. "Real-time gameplay is usually a big divider for classic roguelike fans, as it fundamentally changes the gameplay."

Roguelikes are a type of game that you can really get obsessive about

Darren Grey

Grey gets especially annoyed when he pages through the roguelike filter on Steam, and watches the keyword fill up with games that he has no personal use for. That alone is a strong argument for a partition in the terminology—to establish an orthodoxy to permanently separate the Likes and Lites—but as the catalogue swells, it's also undeniable proof that the old guard is growing increasingly outmoded. There are still plenty of people developing classic roguelikes, but it is undeniable that games like Dead Cells are slowly but surely redefining the term. Grey notes that Hades probably has more players than the entire ASCII roguelike contingency as a whole. It's a losing battle.

"This puts people on the defensive, generating a sort of cultural siege mentality," says Grey. "If you only want to play turn-based games that prioritise thought over reflexes it is now far far harder to find appealing games amidst the noise. It would just be easier if all this new stuff was called something else."

Still, people like Grey are a long way from conceding ground. That's one of the ironies about the traditional roguelike community; for as tedious as these taxonomic deliberations can be, they're destined to continue on forever. It's almost as if there is an enduring faith that with enough ink, and podcasts, and Reddit threads, the community could eventually find a definitive genre truth that everyone could settle on. Maybe that's due to the nature of roguelike game design—which as we've expressed, is bound by a number of fiddly dogmas that don't hinder the other tabs on Steam. (Though the moderators I spoke to both expressed how a similar contentiousness could've existed for FPSes in an alternate history, if they were still being called "Doomclones" in the 21st century.) But Ge has an alternative theory. Maybe roguelike lifers are eager to compartmentalize their videogames, because roguelike lifers have something in common on a genetic level.

"The propensity to discuss this particular topic in so much detail also likely stems from the type of players who enjoy traditional roguelikes in the first place, a pretty analytical, detail-oriented bunch," says Ge. "A huge portion of which are themselves programmers or at least work in IT fields and are big on breaking things down and categorizing them as part of a problem-solving process."

Ge is right. There is certainly a prickly, restless exterior to the average hardcore roguelike fan, and their coterie has been stricken with a confrontational impulse for a long time. But don't let that scare you off. Trust me, for as exclusionary and defensive as this community can appear, the denizens of r/roguelike genuinely love these games—and despite the anxiety, they want you to love them too. (You know, as long as you're playing on their terms.) Could Roguelike Nation be a little kinder to newbies and a little more lenient on some of their more hard-line demands? Probably, but they're the last flag bearers of a tradition worth holding on to, and they take that seriously.

"Roguelikes are a type of game that you can really get obsessive about, and that's not very frequent among single player games. In the whole field of gaming they represent the biggest set of cerebrally-focused challenges," says Grey. "Whatever we end up calling the classic roguelike genre, it shouldn't be forgotten."

via IFTTT

Post a Comment